Tariffs, Tech, and the New Industrial Revolution: How a 145% China Tariff Is Ushering in AI-Powered Manufacturing

Lead: When the United States slapped a staggering 145% tariff on Chinese imports, it sent shockwaves through global markets. Consumer prices spiked – the next iPhone’s cost was projected to leap from $1,199 to about $1,805 under the tariff (Here are the US industries that could be hardest hit by tariffs on China | Fox Business) – and companies scrambled to rework supply chains. But beneath the immediate turmoil, a deeper transformation is underway. Rather than simply bringing factory jobs back to America, this trade rupture is accelerating a new paradigm: AI-driven automation and robotic labor are rising to fill the gap. In an ironic twist, tariffs meant to punish China’s exports may end up triggering a tech-fueled manufacturing renaissance in the U.S. – one that could reshape the global economy for decades to come.

Tariff Shock: From Trade War to Robot Revolution

The sheer scale of the tariff hike is unprecedented. In early 2025, the U.S. dramatically raised import duties on Chinese goods to a composite rate of 145% (Tariffs on Chinese Imports Reach 145%) (Supply Chain Exposure to China Just Got More Serious – Zero100) – a level unheard of in modern trade relations. This “shock therapy” in the ongoing trade war instantly made Chinese products astronomically expensive in the U.S. market. American businesses that source heavily from China faced a stark choice: swallow enormous cost increases or find alternatives. The U.S. imported about $440 billion in goods from China in 2024 (Supply Chain Exposure to China Just Got More Serious – Zero100) (roughly 13% of total U.S. imports), so nearly every sector felt the jolt – from electronics and machinery to apparel and furniture. Economists liken the tariff’s impact to “throwing sand in the gears” of global trade, making everything less efficient and pricier (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). In fact, a World Bank analysis finds that even a 1% increase in tariffs can cut total U.S. trade by about 7.3% (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications). It’s no surprise, then, that a 145% hike has U.S.-China trade plummeting and companies urgently rethinking their supply lines.

But here’s the paradox: these tariffs, touted as a way to bring back American jobs, are more likely to bring back American factories – run by robots. As one Oxford economist points out, with labor costs far higher in the U.S. than in Asia, companies have “an even stronger economic incentive to find ways of automating even more tasks” if they relocate production to the U.S. (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). In other words, when cheap Chinese labor is no longer accessible, AI and robotics become the next best option. Early evidence backs this up: rather than hiring droves of new workers, many firms are exploring investments in automation technology to offset rising costs. “There’s no reason whatsoever to believe that this is going to bring back a lot of jobs,” says economist Carl Benedikt Frey; instead, it will speed up incentives to automate (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME).

Indeed, the last major U.S. tariff wave (in 2018) led to higher production costs and some job losses – without significant automation gains at the time (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). But 2025 is different. AI and robotics have advanced dramatically in recent years (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME) (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). Machines are smarter, more adaptable, and cheaper, lowering the barrier for automation in manufacturing. If the tariffs persist, companies will have “no choice but to bring some of their supply chains back home – but they will do it via AI and robots,” predicts Daron Acemoglu, a MIT economist who studies technology and employment (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME) (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). In the short run, turmoil and uncertainty may delay big capital projects (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). But in the medium term, a robot revolution in American factories is a very real prospect.

The End of “Made in China”? China’s Labor Model Under Threat

For decades, China’s economy has been built on the power of mass human labor – hundreds of millions of workers powering factories that supply the world. This labor-based model turned “Made in China” into a global standard, fueling China’s rise to the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. But the U.S. tariff tsunami – combined with leaps in automation – is undercutting that model. If Western companies no longer need China’s cheap workforce (because robots and AI can do the job elsewhere), China’s long-held export leverage could erode permanently.

There are signs this shift was already beginning. In 2023, U.S. imports from China plunged by 13%, the sharpest drop in 30 years (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge ). China’s total exports actually fell 4.6% in 2023 – the first decline in seven years (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge ) – as global companies diversified to “China+1” locations and domestic demand in the West cooled. By 2024, China exported more to Southeast Asia than to the United States (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge ), a remarkable reversal that speaks to a slow decoupling of the two economies. Now, with the 145% tariffs, that decoupling has accelerated into a full sprint. “U.S. manufacturing is coming home,” notes industry expert Harry Moser, who tallies that roughly 2 million manufacturing jobs have been reshored to America since 2010 amid rising geopolitical risks and new industrial policies (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge ).

For Beijing, this trend is a serious concern. China’s competitive edge of low-cost labor was already diminishing as wages rose and the workforce began aging. (Chinese factory wages have more than tripled in the past decade in many regions, narrowing the gap with the U.S.) Now, automation threatens to leapfrog labor entirely. A World Bank report observes that modern production tech – like industrial robots – “reduced the dependency on low-cost labor and made it feasible to bring manufacturing back” to higher-cost countries (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications). In other words, cheap labor is no longer the trump card it once was. Developing countries like China (and Mexico) face a new threat: advanced automation in rich countries can undercut their manufacturing-led growth model (US–China Economic Rivalry and the Reshoring of Global Supply …).

China is not blind to this challenge. In fact, it has been investing heavily in automation at home, partly to upgrade its own factories and partly as a response to labor shortages. China now leads the world in industrial robot adoption – installing over 276,000 robots in 2023 alone (51% of all new industrial robots worldwide) (Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics). Its robot density (robots per 10,000 workers) has surged past that of the United States, reflecting an aggressive push toward automated manufacturing (China Overtakes Germany and Japan in Robot Density – IFR reports). Some Chinese factories have even implemented “lights-out” production lines – famously, a fully automated smartphone parts plant in Dongguan runs virtually with no human workers on site (Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home | Automation World).

Yet, even as robots spread across Chinese factory floors, there’s a catch: automation in China could undercut the very employment base that underpins social stability and consumer demand. Chinese tech leaders are growing anxious about AI’s impact on jobs. In March 2025, a delegate to China’s National People’s Congress openly called for a special “AI unemployment insurance” to protect workers whose jobs are displaced by automation (As AI disrupts China jobs, could a dedicated insurance fund protect workers? | South China Morning Post) (As AI disrupts China jobs, could a dedicated insurance fund protect workers? | South China Morning Post). He noted that recent leaps in AI (such as powerful new AI models from startup DeepSeek) sent “shock waves through the job market, with companies already planning lay-offs as automation takes over repetitive tasks” (As AI disrupts China jobs, could a dedicated insurance fund protect workers? | South China Morning Post). In short, China faces a dual dilemma: lose manufacturing orders if it doesn’t automate, or risk domestic upheaval if it does.

The long-term implication is sobering for Beijing: if U.S. and Western firms re-shore production with AI and robots, China’s export machine could slow to a crawl. Its leverage over the U.S. (and global markets) derived from being an indispensable supplier would weaken. Factories might close or relocate, and millions of industrial jobs could vanish over time. Oxford Economics projects that by 2030, up to 20 million manufacturing jobs could be lost to robots globally – with China likely bearing the largest share of that impact (The pandemic is accelerating the rise of the robots and changing …). For an economy that still relies on manufacturing for nearly 30% of its GDP, this is nothing short of an existential challenge.

Rise of the Robo-Factories: Rebuilding American Industry with AI

In the United States, meanwhile, a new vision of manufacturing is taking shape. It’s not a return to the 1950s assembly line, jam-packed with human workers – those days are long gone (manufacturing employment fell from 25% of the U.S. workforce in the 1950s to just 7% today) (Can Tariffs Bring American Factories Back To Life?) (Can Tariffs Bring American Factories Back To Life?). Instead, it’s about high-tech “smart factories” populated by robotic arms, automated guided vehicles, and AI-driven control systems. Think fewer human line workers, more robot technicians and software engineers. The goal: build more at home without ballooning labor costs, using automation to stay competitive.

This transition was already underway, but the tariff shock is acting like jet fuel. Companies that once offshored for cheap labor now find themselves calculating the cost of robots versus the cost of a 145% import tax – and often, the robots win. “Automation will always beat labor if it can be designed to replicate and deliver good quality product,” observes supply chain expert John Gattorna (Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home | Automation World). That calculus, combined with the need for speed and resiliency, is driving production closer to the end customer. “The promise of lower manufacturing costs enabled by automation, [and] an increasing need to innovate quickly, [are] driving manufacturing closer to the place of consumption,” Gattorna explains (Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home | Automation World). In short, why make it 8,000 miles away and pay tariffs, if you can automate and make it next door?

Even tech giants known for global supply chains are reconsidering. Apple, for instance, still sources heavily from China, but to avoid a huge tariff disadvantage it may need to localize more production in places like the U.S. or India. Insiders note this “won’t be an easy or fast transition” and will require deep investments in robotics and digital skills for the local workforce (Supply Chain Exposure to China Just Got More Serious – Zero100). Automakers are doing the same math for electric vehicles and batteries, many of which currently rely on Chinese components. Recent U.S. laws like the Inflation Reduction Act already incentivize domestic battery production (for tax credits), and tariffs add another push. The result: a wave of new battery gigafactories and EV plants being built on U.S. soil, designed with state-of-the-art automation in mind.

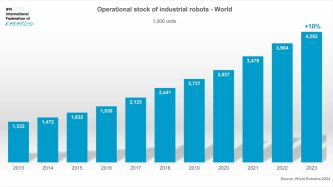

Crucially, the technology is ready (or nearly so) to support this AI-powered industrial renaissance. Modern industrial robots can perform not just repetitive welding or painting, but increasingly complex tasks thanks to advances in machine vision and AI. They’re bolstered by the Industrial Internet of Things (IoT), which networks machines together for optimal efficiency, and even generative AI that can help design better production processes. According to the International Federation of Robotics, there are now over 4 million industrial robots working in factories worldwide (Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics) – double the number from just seven years ago. Robots are getting cheaper and more capable each year. As one AI entrepreneur notes, applying new general AI models to robotics means it “doesn’t require much special effort to apply robots to new purposes now… even mid-sized manufacturers can automate a lot with less effort” than before (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME) (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME).

(Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics) Figure: The global stock of industrial robots has been rising exponentially, reaching about 4.28 million units in operation in 2023 (Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics). As robots become more affordable and AI-powered, companies are leveraging them to bring manufacturing closer to home without sacrificing cost-efficiency. Automation allows producers to operate in high-wage countries like the U.S. while still keeping unit costs competitive (Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics).

Alongside robotics, artificial intelligence is revolutionizing how factories are run. AI-driven systems can optimize supply chains, predict maintenance needs, and adjust workflows in real time. For example, AI-based quality control can spot defects faster than any human, reducing waste. These technologies together enable what analysts call the “lights-out factory” – a production site that can operate 24/7 in the dark, with minimal human oversight. While fully autonomous factories are still rare, many plants are moving toward that model for at least part of their operations. The benefit is not just labor savings: such facilities also tend to be safer, faster, and highly adaptable to design changes (a key advantage as product life cycles shorten in the tech age). A recent analysis by PwC identified robotics, IoT, augmented reality, and 3D printing as four key technologies making domestic advanced manufacturing possible (Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home | Automation World) – all areas where the U.S. is investing heavily.

The U.S. government, for its part, is actively laying groundwork for this next industrial revolution. The CHIPS and Science Act is funneling over $50 billion into domestic semiconductor fabs and R&D, aiming to secure the tech infrastructure needed for AI and automation leadership. Policymakers talk of a future where AI “makes our workers more productive” rather than replacing them (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME), and they are betting big on tech to revitalize industry. “We refuse to view AI as a purely disruptive technology that will inevitably automate away our labor force,” declared the U.S. Vice President in 2025, arguing that with the right policies AI can “make our workers more productive” and drive broadly shared gains (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). To that end, federal incentives are encouraging companies to build new high-tech plants in America’s heartland – from Ohio to Texas to Arizona – often with a focus on cutting-edge automation and robotics from day one.

Make no mistake: this paradigm shift won’t recreate the mass employment manufacturing once provided. Many of the new U.S. factories will employ far fewer people than the factories of old, albeit in more skilled roles. But they could reboot America’s industrial base in terms of output and strategic capacity. By localizing production of everything from microchips to medical supplies to electronics, the U.S. reduces its vulnerability to overseas disruptions and positions itself as a leader in 21st-century industry. As one Forbes analysis put it, embracing AI and advanced manufacturing is key to “revitalizing America’s industrial might” and reclaiming a lead in the next industrial revolution (Revitalizing America’s Industrial Might: Harnessing AI To Lead The Next Industrial Revolution) (Revitalizing America’s Industrial Might: Harnessing AI To Lead The Next Industrial Revolution). It’s a new kind of industrial might – measured not just in number of workers, but in technical prowess, productivity, and resilience.

The Future of Work: Fewer Jobs or New Kinds of Jobs?

One of the most profound questions raised by this shift is: What happens to workers? If robots and AI take over a larger share of manufacturing, the worry is a net loss of jobs and greater inequality. Indeed, history shows that heavy manufacturing automation can decouple productivity from employment – factories produce more with fewer hands. The tariff-driven rush to automate could therefore displace certain jobs permanently. Oxford Economics estimates that robot automation could displace up to 8.5% of the global manufacturing workforce by 2030 (The pandemic is accelerating the rise of the robots and changing …). In the U.S., many of the jobs that were offshored in the past may return in form but not in headcount. A plant that might have employed 1,000 assemblers in the 1990s might employ 100 technicians and engineers in 2030, supervising an army of machines.

However, it’s not as simple as humans versus robots. New categories of jobs are emerging alongside the automation wave. Demand is already rising for robotics engineers, maintenance specialists, AI programmers, data analysts, and logistics experts to build and run these smart factories. For every repetitive task automated, there may be a new task of programming or oversight created. A recent analysis by the Christian Science Monitor noted that the current U.S. manufacturing mini-boom (in areas like electric vehicles and chips) is bringing slightly more jobs than it displaces – but critically, “such as robot technicians” rather than assembly line workers (A new US manufacturing boom may bring more AI than jobs). The workforce will need to reskill and adapt. Instead of manual dexterity, sought-after skills will include digital literacy, problem-solving, and the ability to work alongside automated systems (often referred to as “human-machine collaboration” or cobotics).

There’s also a geographic element. Manufacturing jobs of the past supported entire communities, often in the Midwest and South. The new automated plants may not require as many workers, but they do require an ecosystem of suppliers, contractors, and service providers, which can create additional employment indirectly. Moreover, if the U.S. successfully scales up industries like semiconductor fabrication, battery production, and advanced machinery, it could spur a supporting job boom in construction, education (training programs), and R&D. Already, large tech manufacturing investments (like new chip fabs in Arizona or car plants in Georgia) are leading to local investments in technical colleges and vocational programs to build the talent pipeline.

Nonetheless, social challenges remain. The transition could be painful for workers without the skills to participate in the new paradigm. There is a risk that older workers or those in regions heavily dependent on low-skill manufacturing could be left behind. Policymakers may need to consider measures like stronger social safety nets, unemployment support (much as Chinese officials are considering an AI unemployment fund (As AI disrupts China jobs, could a dedicated insurance fund protect workers? | South China Morning Post)), and massive upskilling initiatives. In the best case, humans will be freed from drudge work and move into safer, more creative roles while machines do the heavy lifting. In the worst case, inequality widens, with profits accruing to owners of technology and many workers stuck in low-wage service jobs with the manufacturing ladder kicked out from under them. The likely outcome will depend on how society manages the change – through education, policy, and perhaps new ideas like a shorter workweek or universal basic income if productivity surges make a 40-hour factory workweek obsolete.

From a labor relations perspective, increased automation could also shift power dynamics. During economic downturns, companies often seize the opportunity to adopt more automation – using technology to break through previous labor constraints or union bargaining power (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME). If robots become an easy substitute, workers may have less leverage to demand higher wages or better conditions, potentially weakening unions further. On the flip side, if managed well, the productivity gains from automation could translate into higher wages for the skilled workers who remain, and lower prices for consumers, effectively raising living standards. Productivity growth is the ultimate source of long-term prosperity, and AI/robotics promise a lot of it – the question is how the gains are distributed.

Economic and Geopolitical Power in an AI-First World

On the global stage, the rapid shift to AI-powered manufacturing is poised to reorder economic power. If the United States successfully marries automation with a resurgence in domestic production, it could regain a degree of manufacturing self-sufficiency not seen in generations, reducing trade deficits and strengthening its industrial base. This comes with strategic advantages: supply chain security, less dependence on geopolitical rivals for critical goods, and a stronger position in setting global technology standards. Some analysts suggest we are entering a new technological Cold War, where national strength is measured in chips and robots as much as in tanks and missiles.

Consider the technology “arms race” between the U.S. and China. The U.S. isn’t just imposing tariffs; it’s also aggressively restricting China’s access to cutting-edge tech. In late 2024, Washington unveiled sweeping export controls aimed at “strangling” China’s high-tech industries – blocking the sale of advanced AI chips, chip-making equipment, and design software to Chinese firms (Choking off China’s Access to the Future of AI). These moves, unprecedented in scope, seek to deny China the tools to excel in AI and semiconductor manufacturing, thereby slowing its progress in critical automation and military technologies (Choking off China’s Access to the Future of AI). One U.S. official described it as retaining control of “chokepoint” technologies and “strangling [China’s] technology industry – strangling with an intent to kill” (Choking off China’s Access to the Future of AI). While the rhetoric is extreme, it underscores how high the stakes have become. Leadership in AI and robotics is now seen as a zero-sum game tied directly to national power.

China, for its part, is doubling down on self-reliance and innovation. Beijing’s industrial plans (such as “Made in China 2025”) have long aimed to leapfrog into advanced manufacturing and dominate fields like robotics and AI. In some areas, China is making rapid strides – for example, it leads in electric vehicle production (which increasingly involves automation) and has world-class AI research. Chinese companies like DJI (drones) or Hikvision (AI surveillance hardware) show that the nation can be a global leader in tech manufacturing. The big question is whether China can overcome Western trade barriers and its own economic headwinds to transition from the “world’s factory” to the “world’s innovator.” If it can apply AI/robotics across its industries faster than the U.S., it might retain an edge. If not, it could see a slow loss of manufacturing clout as other countries gain.

Other nations will also be swept up in this transformation. Allies and neighbors: Countries like Mexico, Vietnam, India, and Indonesia are currently beneficiaries of the shift away from China – absorbing some of the manufacturing business with their cheaper labor. U.S. imports from Vietnam, Mexico, and others have surged as China’s share declined (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications). In the near term, these countries gain. But in the longer term, they too could face the automation dilemma. If the cost of robotics continues to fall and the U.S. and Europe onshore more production, will there be as much investment flowing into low-wage countries? The nations that thrive will be those that master technology and logistics: a World Bank study finds that countries with higher labor productivity, strong infrastructure, and technological readiness are best positioned to become new manufacturing hubs in this restructured landscape (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications) (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications). This suggests places like Eastern Europe (with skilled labor and EU proximity) or South Korea and Japan (tech powerhouses) might capture value, whereas purely low-cost producers could struggle unless they climb the value chain.

Geopolitically, we might see a further crystallization of blocs. The U.S. and its allies could form a tighter technological alliance – sharing innovations in AI, coordinating on standards and ethics, and ensuring each other’s supply chains for critical items (such as semiconductors or medical equipment) are resilient. China, in response, may deepen ties with other emerging economies, exporting its own automation tech and trying to build an alternative sphere of influence (for instance, through the Belt and Road Initiative’s digital and industrial projects). In a scenario where trade in goods is less central (because more is made domestically or regionally with automation), competition may shift to trade in technology and services. We may see contests over whose AI platforms are adopted globally, whose operating systems run the robots, and who patents key breakthroughs in energy efficiency or materials that could give an industrial edge. The balance of economic power in 2035 might thus be determined by innovation ecosystems and control over critical tech supply chains, more than by who has the cheapest workers or largest factories.

Automation and the Environment: A Greener Paradigm?

An often underexplored facet of this shift is its impact on sustainability and carbon emissions. Could AI-powered local manufacturing be better for the planet? There are reasons to think it might. For one, producing goods closer to where they are consumed cuts down on long-distance shipping. Today, about 80% of world trade by volume travels by sea, and maritime shipping accounts for roughly 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Bold global action needed to decarbonize shipping and ensure a …). A reduction in container ships crisscrossing the ocean – because more products are made in the U.S. or assembled in Mexico for the U.S. market – directly translates to lower fuel use and lower emissions. In addition, shorter supply chains mean less inventory sitting in warehouses (which often requires heating/cooling) and less spoilage or waste from transit damage.

Inside the factories themselves, automation can drive big efficiency gains. Robots, unlike humans, don’t need climate control or bright lighting on the factory floor. “Lights-out” facilities can literally go dark and unheated, saving electricity – one reason lights-out manufacturing is touted as improving the environmental footprint (The Shift to Fully Automated Factories: Embracing Lights-Out …). Modern robotic systems are also incredibly precise, which reduces material waste (e.g. fewer off-spec products that get scrapped). And AI-driven analytics can optimize energy usage, turning machines off when idle and smoothing out peak electricity loads. According to one study of Chinese manufacturers, a 1% increase in robot density was associated with a 0.018% decrease in carbon emissions intensity, as automation promoted more efficient processes and innovation (The effect of automation on firms’ carbon dioxide emissions of China | Digital Economy and Sustainable Development ). That may sound small, but scaled up across an economy it becomes significant – especially as factories account for a large share of energy usage. The International Energy Agency estimates that new efficiency technologies (many of which involve automation and digital control) could help cut industrial CO2 emissions by up to 70% in the coming decades (Industrial automation is the key to addressing the energy and climate crises). In short, smart factories tend to be greener factories.

Furthermore, bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. could dovetail with the clean energy transition. Many of the new automated plants breaking ground in America are being paired with renewable power sources. For example, some data centers and factories are being built next to solar farms or wind turbines to ensure a supply of green energy. Industrial clusters can also make use of local resources (like recycling waste heat to warm nearby buildings, etc.) more effectively than an isolated overseas supplier could. Additionally, producing domestically under U.S. environmental regulations can avoid some of the pollution problems seen in unregulated factories abroad. (China has struggled with industrial pollution and carbon emissions partly because of its massive manufacturing output for export; a portion of those emissions effectively get “outsourced” when rich countries import goods. Reshoring production means taking back that responsibility, but also the opportunity to produce more cleanly.)

That said, automation is not automatically green. Robots and AI systems consume plenty of power – server farms to run AI, electricity for machines – so the source of that power matters. If an automated factory runs on coal power, it could negate many efficiency gains. Also, the production of robots and electronics has its own carbon footprint and resource demands (e.g. mining of rare earth metals). There’s a scenario to avoid: one where we simply relocate emissions or even increase them due to energy-intensive automation. To truly realize a carbon benefit, the rise of robotic manufacturing needs to be coupled with the rise of clean energy. Encouragingly, this seems to be the direction of policy. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act not only incentivizes domestic manufacturing but does so specifically for green technologies (solar panels, EV batteries, etc.), tying together the automation trend with decarbonization goals.

In the big picture, a world of more localized production could reduce the overall carbon intensity of the global economy. Less freight transport, more state-of-the-art factories using best-in-class efficiency tech, and faster diffusion of eco-friendly innovations via digital networks are all positive signs. Moreover, AI can help design more sustainable products – for instance, by simulating thousands of material combinations to find a lighter, stronger alternative that reduces waste. The convergence of AI, robotics, and sustainability might even enable concepts like the circular economy to flourish, with local automated facilities recycling old products into new ones seamlessly.

5–15 Years Out: A Glimpse at 2030 and Beyond

Fast forward a decade: what might the global economic landscape look like if these trends continue? While crystal balls are always cloudy, current indicators offer some grounded projections:

- A New Manufacturing Map: By 2030, the U.S. could be producing a much larger share of what it consumes, especially in technology-intensive sectors. We may see a resurgence of “Made in USA” – not in every gadget or garment, but in strategic goods like semiconductors, energy storage, pharmaceuticals, and aerospace components. America won’t be alone; Europe and Japan are similarly investing in automation to shore up domestic industries. China, meanwhile, might pivot to focus more on its huge domestic market and on higher-end exports (like its own advanced machinery) as its low-end export volumes decline. Global supply chains will likely be more regionally focused: Americas, Europe, and Asia forming more self-contained loops.

- China’s Economy Transformed: Faced with waning export growth, China will likely accelerate its transition to a consumption-driven economy. We could see higher automation within China’s factories to stay competitive, even as export orders drop. The result might be a paradox of higher productivity but lower employment in manufacturing. China’s growth rates, already projected to fall to ~2–3% by 2030 (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge ), could stabilize at a lower level. Politically, this may force difficult reforms or increased social spending to keep unemployment in check. There’s also the possibility that China doubles down on technological innovation to escape the middle-income trap – for example, becoming a global leader in AI software, clean energy tech, or biotech, to compensate for losses in basic manufacturing. Its success or failure in that endeavor will heavily influence its standing as a superpower.

- Global Labor Market Shifts: The period of 5–15 years from now may be remembered as the time when the nature of work fundamentally changed for millions. In manufacturing, the trend is toward fewer total jobs but more high-skilled jobs. Many routine jobs in assembly, packaging, inspection, and even forklift operation will be done by machines. Human roles will concentrate in what machines can’t (yet) do well: complex integration, customization, oversight, maintenance, and design. The skills gap could become a gaping chasm if education and training don’t keep up – a top challenge for policymakers will be re-training mid-career workers and preparing young people for an AI-augmented workplace. The service sector, too, will feel the ripple effects, as automation spreads from factories to warehouses, retail, and even fast food (think robotic baristas, AI cashiers, etc.). Society may need to rethink how we value and compensate work, as well as how to support those whose roles vanish. In an optimistic scenario, productivity growth from automation yields such economic gains that governments can afford stronger safety nets or reduced working hours without hurting living standards. A less optimistic scenario could see technological unemployment contributing to social unrest or widening class divides.

- Techno-economic Dominance: The countries that lead in deploying AI and robotics at scale will likely set the rules for the global economy. If the U.S. maintains its lead in AI research and combines it with manufacturing prowess, it might inaugurate a new Pax Technologica – a period where American standards and companies dominate the advanced industries (much like it did in the mid-20th century, but with different industries at the forefront). We could see U.S. tech giants extending their reach into manufacturing (imagine Google or Microsoft AI platforms running factories worldwide) and industrial giants like GE or Siemens reinventing themselves as AI companies as much as manufacturing ones. Conversely, if China finds ways around the tech blockade and pushes ahead in industrial AI, it could leverage its massive domestic data and market scale to come roaring back, perhaps in new sectors (China is already a global leader in renewable energy tech and could dominate in robotics by sheer volume). The race is on, and the outcome will shape alliances: expect more talk of “technological sovereignty” in Europe, “friend-shoring” among like-minded democracies, and continued jockeying at international bodies over tech standards and trade norms.

- Daily Life in the Automation Age: For the average person, many of these macro changes will manifest in subtle but significant ways. Consumers might notice that certain products become cheaper or more custom-tailored as local automated manufacturing cuts costs and production runs shorten. You might order a product online and have it 3D-printed or assembled by robots at a facility near your city, ready for pickup later that day. Jobs might require more interaction with AI – factory technicians could diagnose issues with the help of an AI assistant, or a warehouse worker might supervise a fleet of robots through a control tablet. There may also be fewer human interactions in some services (e.g. autonomous vehicles making deliveries, robotic kiosks at stores), which has cultural and social implications. On the positive side, tedious tasks at work and home could be offloaded to machines, giving people more time for creative, strategic, or leisure activities. On the negative side, people might feel a sense of dislocation or lack of purpose if displaced by automation – a challenge for community and individual well-being that society will have to address.

- Environment and Efficiency: By 2035, if current trends hold, the global economy could be somewhat less carbon-intensive thanks to these shifts. A lot of manufacturing will be energy-optimized and closer to end-use, meaning fewer emissions from transport. Renewable energy could be powering a significant share of automated factories. We might even reach the point where manufacturing output grows while absolute emissions fall – a decoupling that is crucial for meeting climate goals. Smart grids, smart factories, and smart logistics (all AI-managed) will squeeze out waste. However, one must consider rebound effects: cheaper production can sometimes spur more consumption (if goods get cheaper, people might buy more, offsetting some gains). Net impact will depend on parallel progress in conscious consumption and global carbon agreements.

Underneath it all, one theme is clear: the 145% China tariff may be remembered as a catalyzing moment – a shock that hastened the arrival of a new era. Just as earlier industrial revolutions were spurred by crises or innovations (the wartime mobilization that advanced mass production, or the internet boom that followed the tech race of the Cold War), today’s trade conflict is turbocharging the adoption of automation and AI in manufacturing. We are witnessing the birth of a techno-industrial revolution in real time, with profound implications for economic power, work, and the world order.

It’s a future full of promise – factories humming on renewable energy, products made efficiently onshore, workers freed from drudgery – but also one fraught with pitfalls – displaced workers, new global rivalries, and difficult adjustments. Navigating this future will require foresight from leaders, adaptability from businesses, and resilience from workers and communities. The only certainty is that we’ve crossed the threshold into a new paradigm. The old playbook of globalization is being rewritten by algorithms and automation. And as the dust settles from the tariff-induced shake-up, the countries and companies that master this new paradigm stand to reap immense rewards, while those that cling to the past may find themselves left behind in the factories of history.

Sources:

- Fox Business – “US Industries that could be walloped by China tariffs” (April 2025) (Here are the US industries that could be hardest hit by tariffs on China | Fox Business)

- TIME – “Trump Wants Tariffs to Bring Back U.S. Jobs. They Might Speed Up AI Automation Instead” (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME) (Trump’s Tariffs Could Boost AI, Not U.S. Jobs | TIME)

- National Marine Manufacturers Assoc. – “Tariffs on Chinese Imports Reach 145%” (Apr 11, 2025) (Tariffs on Chinese Imports Reach 145%)

- Zero100 Supply Chain Analysis – “Tariffs to 145% and supply chain exposure” (Apr 10, 2025) (Supply Chain Exposure to China Just Got More Serious – Zero100) (Supply Chain Exposure to China Just Got More Serious – Zero100)

- Investopedia – “Can Tariffs Bring American Factories Back to Life?” (Apr 9, 2025) (Can Tariffs Bring American Factories Back To Life?) (Can Tariffs Bring American Factories Back To Life?)

- International Federation of Robotics – World Robotics 2024 Report (Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics) (Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics)

- World Bank – “From offshoring to reshoring” trade analysis (2023) (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications) (The shifting landscape of global manufacturing: From offshoring to reshoring and its welfare implications)

- AMT (Harry Moser) – “U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports Plunge” (Apr 2024) (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge ) (U.S. Reshoring Surges as China’s Exports to the U.S. Plunge )

- South China Morning Post – “AI disrupts China jobs, call for insurance fund” (Mar 2025) (As AI disrupts China jobs, could a dedicated insurance fund protect workers? | South China Morning Post)

- Oxford Economics via CNBC – Robots could displace 20 million jobs by 2030 (The pandemic is accelerating the rise of the robots and changing …)

- Automation World – “Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home” (Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home | Automation World) (Automation Brings Manufacturing Back Home | Automation World)

- CSIS – “Choking off China’s Access to AI (Tech Export Controls)” (Oct 2022) (Choking off China’s Access to the Future of AI) (Choking off China’s Access to the Future of AI)

- Springer (Yue Lu et al.) – Automation and CO2 emissions in Chinese firms (2023) (The effect of automation on firms’ carbon dioxide emissions of China | Digital Economy and Sustainable Development )

- UNCTAD / IMO – Data on shipping and emissions (Bold global action needed to decarbonize shipping and ensure a …)

- Economist Impact – “Industrial automation key to climate crises” (2023)